I started my research by looking at existing papers which investigate different aspects of Forests Acoustics. This was chosen to be the starting point of this project in order to familiarise with the field, and break it down into different components.

Forest Acoustics

The topic was primarily addressed by Carl F. Eyring in 1946 with his study of “Jungle Acoustics”, focusing on the different physical properties of the jungle such as temperature, wind velocity and humidity, and their effect on the timbre and sense of direction of sound [1]. His publication approached the forest as a whole, showing some of its interesting acoustic characteristics, which inspired several researchers towards investigating the way in which sound behaves within such an environment.

In 2001, a different approach was taken by Sakai, who investigated the acoustics of a bamboo forest [2]. After noticing some interesting characteristics on the projection and reverberation of sound in such an environment, he conducted acoustic measurements targeted towards obtaining and analysing Impulse Responses. Through performing auralisations, his study showed that music sources with higher frequency components are more appropriate in such an environment.

Virtual Models of Forests

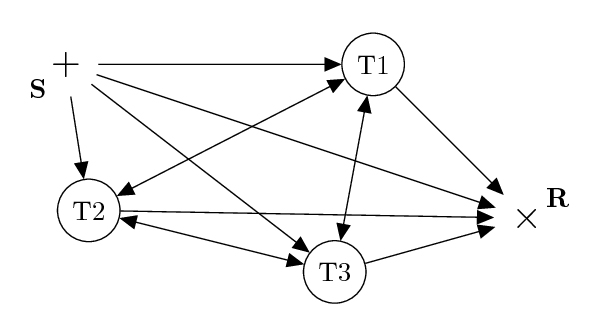

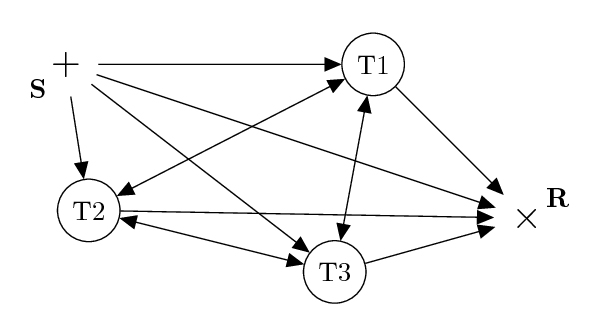

The next two papers approached the topic using virtual representations of a forest to obtain Impulse Response Measurements. The first one used a network of Digital Waveguides named “Treeverb”, to simulate the acoustics of a forest [3]. This paper mainly focused on the effect of the shape of the tree trunk towards the scattering and reflection of sound, by modeling all trees as perfect cylinders distributed randomly in space, with no energy absorption.

Based on that idea, a second paper was published focusing on simulating and studying the acoustics of open-air spaces including forests, using a “Waveguide Web” [4]. This network made use of the Digital Waveguides used in Treeverb, as well as Scattering Delay Networks, resulting into more realistic results. Instead of approaching the trees as perfect reflecting surfaces, the scattering junctions used filtered off the reflected signal to create the effect of sound attenuation.

Conclusion

I chose these papers as my starting point, as the first two papers notice some of the unique characteristics of forests and perform different types measurements, while the next two focus on simplifying the system enough in order to model a certain characteristic of the forest. Taking these into account, I was directed towards Physical Modelling and Digital Waveguide Synthesis. This made me want to obtain a better understanding of artificial reverberation and sound attenuation in a forest. In addition to that, I am currently looking into additional literature to obtain a better understanding on Physical Modelling Synthesis and Digital Waveguides.

Figure: The different paths of sound between a source S and a receiving position R in a forest consisting of 3 Trees, as expressed in “Treeverb Digital Waveguide” [4]

References

[1] Eyring, C. (1946). Jungle Acoustics. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, [online] 18(1), pp.245-245. Available at: https://asa.scitation.org/doi/abs/10.1121/1.1916362

[2] Sakai, H., Shibata, S. and Ando, Y. (2001). Orthogonal acoustical factors of a sound field in a bamboo forest. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, [online] 109(6), pp.2824-2830. Available at: https://asa.scitation.org/doi/10.1121/1.424564

[3] Spratt, K. and Abel, J. (2008). A Digital Reverberator Modeled After the Scattering of Acoustic Waves by Trees in a Forest. In: AES 125th Convention. [online] San Francisco, CA, USA: AES. Available at: http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=14801

[4] Stevens, F., Murphy, D., Savioja, L. and Valimaki, V. (2017). Modeling Sparsely Reflecting Outdoor Acoustic Scenes using the Waveguide Web. In: IEEE/ACM Transactions of Audio, Speech and Language Processing. [online] IEEE. Available at: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/115692/1/modeling_sparsely_reflecting.pdf